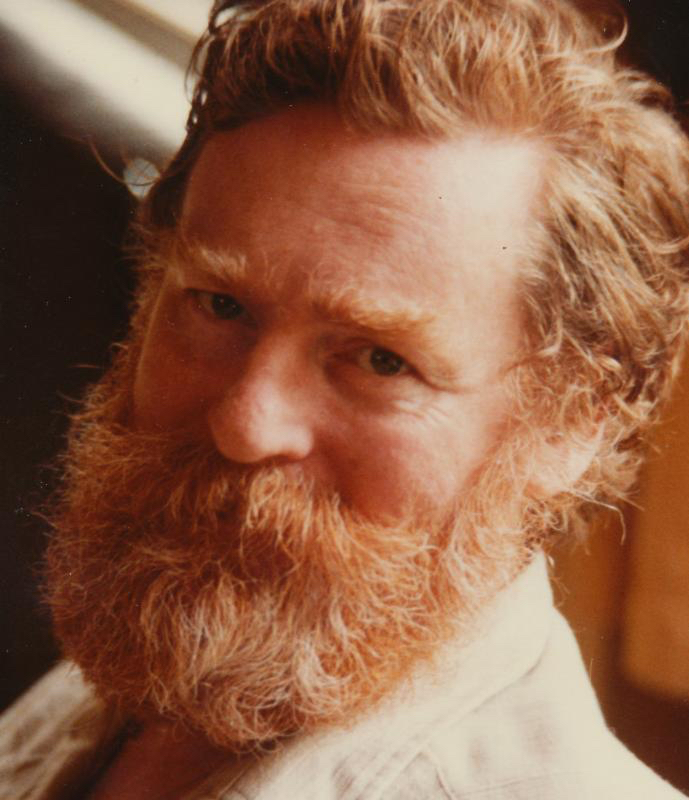

Patrick Watson(September 5, 1935 – September 1, 1992), a senior student of tai chi Grandmaster Cheng Man-ch’ing (Zheng Manqing), was the founding Director of The School of T’ai Chi Chuan, Inc. in New York and the T’ai Chi Foundation. He was also a teacher of swimming and an accomplished actor.

Early years

Watson was born in Minnesota and lived there until the age of four when his family moved west, settling in San Francisco, California, where, from an early age, he excelled in swimming, theater and the martial arts.[1] He spent twenty years as a swimming coach, lifeguard instructor, and teacher of Hawaiian Swimming in San Francisco. He studied theater at the Actor’s Workshop of San Francisco and was a member of the Screen Actors Guild. He served as a consultant for martial arts choreography in a number of films. In addition to his mastery in tai chi chuan, Watson’s attainment in the martial arts included a Golden Sash in Kung Fu and Black Belts in Judo and Kendo. He was also a master of Iaido, the Japanese art of drawing the sword.

Student of Cheng Man-ch’ing

Watson often recounted the time when, while still a child, he was counseled by a teacher in San Francisco to further his skills in the martial arts by seeking a Master of the Five Excellences.[2] He found such a master in Professor Cheng Man-ch’ing, with whom he began studying tai chi chuan in New York City in 1966. Watson was recommended to Cheng through his first tai chi teacher in San Francisco, Master Choy Kam-man, whose father, Choy Hok Ping (1886-1957)—reputedly the first to introduce Yang style tai chi to the United States—had been a fellow student with Cheng of Yang Cheng Fu.[3] Watson soon became a favorite of Professor Cheng who nicknamed him “Baby Elephant Standing on His Head,” a reference both to Watson’s large size and his practice of doing headstands.

(Professor Cheng and Patrick Watson)

He was also a favorite of fellow Northern Californian, Tam Gibbs, Professor Cheng’s translator.

(Tam Gibbs, Ben Lo, and Patrick Watson)

As a new arrival from San Francisco, Watson was considered an “outsider” by some of the New York students. According to Pat Gorman, a senior student of Watson’s who accompanied him to Cheng’s Shr Jung studio in New York in the early 1970s, Watson had a “boisterous jolliness” about him in an era of serious spiritual seeking that turned off some of Cheng’s other students. Patrick Kelly describes Watson as “open, friendly, outspoken and outwardly overconfident in his own ability, all of which had led him into trouble with most of the other senior students of Grandmaster Zheng.”[4]Robert W. Smith, for example, referring to Watson as “Irish” in his Martial Musings, described him as “full of blarney.”[5]Kelly notes, however, that “Grandmaster Zheng himself saw beyond the surface” and treated Watson as “one of his inner circle.”[6]Watson himself recognized the need to work on his own ego-reduction, leading him to regard tai chi as a spiritual path as well as a martial art. Indeed, for all Watson’s exterior bravado, all who knew him acknowledge the incredibly light and non-aggressive quality of his touch in push hands. According to Gorman, Watson’s “pushes” could not be felt, and push hands partners would accelerate away without feeling shoved. In his Taiji Secrets(second edition), Patrick Kelly describes Watson’s touch as the only one of Cheng Man-ch’ing’s students that was as soft as Cheng’s older student, Huang Sheng Shyan(1910-1992). Wolfe Lowenthal recounts how Professor Cheng’s appreciation of Watson’s abilities led him to urge his students to elect Watson to the group of senior students who would direct Shr Jung in Cheng’s absence. When Watson was not elected, Cheng went ahead and appointed Watson to the group of directors, making him the only senior student in Cheng’s line of succession to be directly appointed by Cheng.[7]

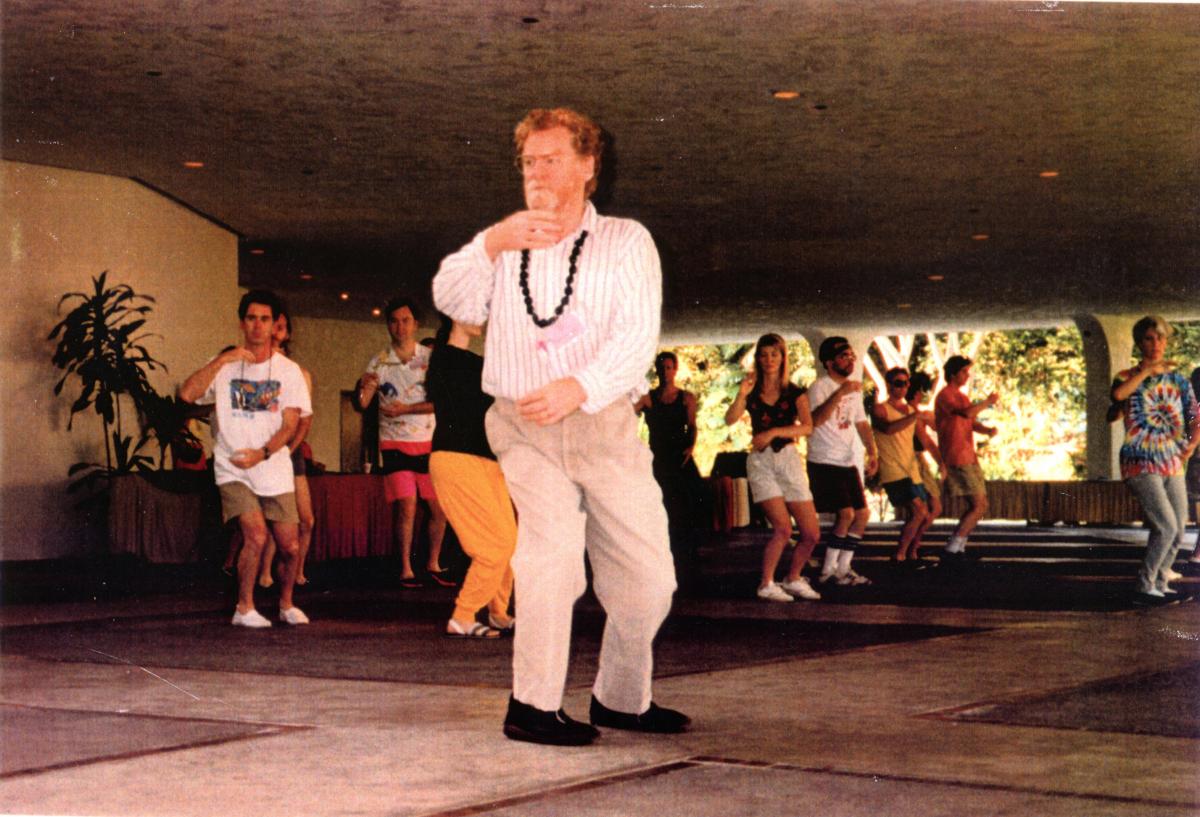

The School of T’ai Chi Chuan and the T’ai Chi Foundation

Watson founded The School of T’ai Chi Chuan in 1975 in New York City shortly after Professor Cheng’s death, taking to heart the two requests Cheng had made of him: (1) to teach teachers of Cheng’s form of tai chi chuan, and (2) to spread tai chi around the world. The Stichting School of T’ai Chi Chuan in the Netherlands was established shortly thereafter. In 1979, Watson set up the non-profit T’ai Chi Foundation, which now supports affiliated teaching centers and conducts teacher-training programs and residential programs throughout the United States, Europe, and Latin America.

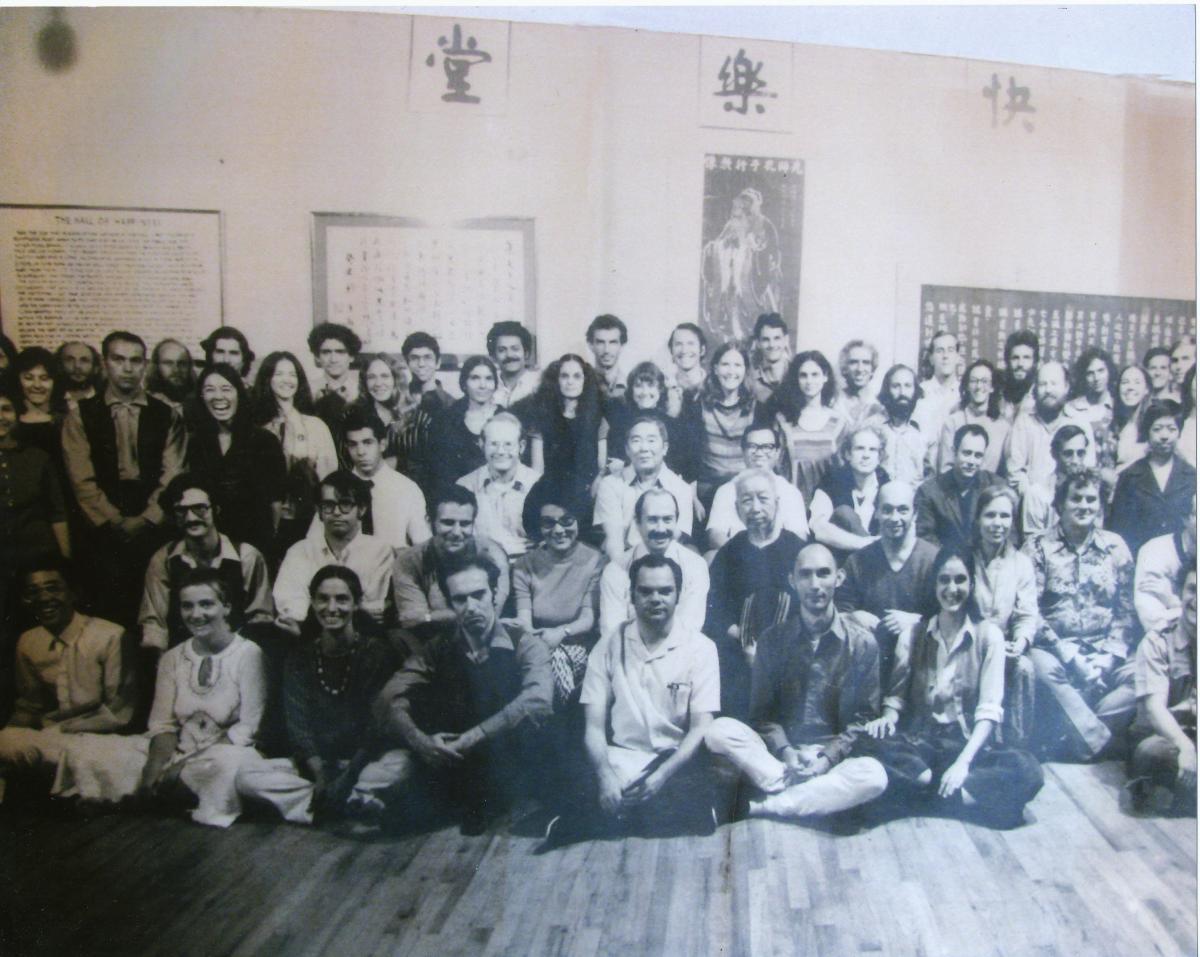

Watson was an innovator in the method of teaching tai chi chuan, attempting to retain what was essential to the tradition while transmitting the movements and principles in a more contemporary, structured way. In collaboration with Pat Gorman, Watson organized the curriculum of The School of T’ai Chi Chuan and the T’ai Chi Foundation into nine distinct levels of advancement. He also introduced a team-teaching method that required instructors to receive feedback from each other. Watson himself encouraged his senior students to give him feedback on his own teaching and public presentations. Such feedback was part of an effort by Watson to cultivate objective self-awareness in himself and his students, and, in general, to promote engagement in ego-reduction and spiritual growth for the benefit of all. In this, Watson was influenced by Oscar Ichazo, founder of the Arica School of human development, with whom Watson studied for many years. Watson was pleased to have introduced Ichazo to Cheng Man-ch’ing in 1972, and he maintained that both tai chi and the Arica work were complementary practices aimed at the clarification and development of consciousness.

(Oscar Ichazo, Cheng Man-ch’ing, and Patrick Watson, with students)

Other examples of Watson’s innovation in the instruction of tai chi include the creation of T’ai Chi Children’s Games and the completion of the development of The Eight Ways of T’ai Chi Chuan. The Eight Ways are a series of postures, movements and walks from Cheng Man-ch’ing that further condensed tai chi principles into a form that is useful and accessible to all. Cheng himself had learned such healing postures from Yang Cheng Fu and practiced them when he had tuberculosis. Cheng continued this practice with his patients, assigning specific moves to be held for periods of time, creating energetic healing for their illnesses. According to Pat Gorman, who documented the process and collected the final instructions, Mrs. Cheng asked Watson and Tam Gibbs to complete the development of the Eight Ways after Professor Cheng’s death. Over time, these movements have proven restorative to aging adults, to people with chronic illness, and to those recovering from injury.

Death and Legacy

Watson died on September 1, 1992, in New York City of renal failure and cardiac arrest due to complications of diabetes. He was survived by his wife, Peggy Watson. Before his death, Watson appointed a group of his senior students to succeed him in carrying on the legacy of his life work—his teachings—and to maintain his school for future generations. These senior students are Pat Gorman, Sherry Kent, Margaret Matsumoto, Margaret Olmsted, Axel Schwolow, Gerrie Sporken, Peggy Watson and Greg Woodson. In the subsequent twenty-plus years, six of the eight “Legacy Holders” have continued to honor Watson through their teaching, writings, speaking tours, program and curriculum development, and overall leadership of the school that he envisioned and built.

(Gerrie Sporken(Standing), Greg Woodson, Sherry Kent(Standing), Peggy Watson, Margaret Matsumoto, Margaret Olmsted(Standing), and Pat Gorman)

Today, the T’ai Chi Foundation, including The School of T’ai Chi Chuan of New York and the Stichting School of T’ai Chi Chuan of Amsterdam, has trained over 500 teachers of t’ai chi, push hands, The Eight Ways, Roots & Branches Qigong, T’ai Chi Children’s Games, the Sword Form, and Pole. In addition, there are special programs, such as Practitioners Healing Qi Gong, designed for medical practitioners to use with their patients, and studies in the Five Excellences and the Classics.

-Written by Andrew Dell’Olio

References

The Tai Chi Press, Journal of the School of T’ai Chi Chuan, Inc. Edited by Alex Carr. 1991-1992.

Patrick Kelly, Infinite Dao(New Zealand: Taiji Books, 2007).

Wolfe Lowenthal, Gateway to the Miraculous: Further Explorations in the Tao of Cheng Man-ch’ing (Berkeley: Frog, Ltd., 1994)

Alex Carr, “Patrick Watson: A Glimpse of a Tai Chi Chieftain,” https://alexgcarr.wordpress.com/2013/08/11/a-glimpse-of-patrick-watson-tai-chi-chieftain/

Randall Unruh, The Indispensable Scarf: Stories and Meaning of Tai Chi Chuan (Los Angeles: World Language Resources, Inc., 2007)

[1]Patrice Wooldridge, Obituary of Patrick Watson, The T’ai Chi Press, Journal of the School of T’ai Chi Chuan, Inc., Vol. I, No. IV 1993. What follows in this section is based on Wooldridge’s obituary.

[2]Conversation with Pat Gorman, June 29, 2016.

[3]Andrew Dell’Olio, “Roots: Interview with Patrick Watson, Part 1,” The T’ai Chi Press, Journal of the School of T’ai Chi Chuan, Inc., Vol. I, No. 1 Summer 1991.

[4]Patrick Kelly, Infinite Dao(New Zealand: Taiji Books, 2007), p. 163. ISBN: 978-0-473-13049-7

[5]Robert W. Smith, Martial Musings: A Portrayal of Martial Arts in the 20thCentury(Erie: Via Media Publishing, 1999). ISBN 1-893765-00-8.

[7]See Wolfe Lowenthal, Gateway to the Miraculous: Further Explorations in the Tao of Cheng Man-ch’ing (Berkeley: Frog Ltd, 1994), pp. 87-89. ISBN 1-883319-13-7. Lowenthal also describes the experience of Watson later in life, even as “an emaciated old man” ailing with kidney failure, “sticking to my center, ever so subtly penetrating and controlling my balance point. He could hardly walk, and yet there he was, with me floating on his arm like a balloon on a string” (p. 89).

Dịch

Dịch